Many of us doubt others, thinking about what their agendas might be. That is a massive problem with humans because trust is not automatic; it is earned. In this episode, Michael Hingson, a #1 New York Times bestselling author and international lecturer, shares his insights on how critical trust and communication work in teamwork. He also shares the 9/11 story, which showed what kind of a leader Michael is. Michael embodied a mindset of preparing for an imminent danger before it happens. Because of his presence and ability to communicate, build trust, and develop teamwork he was able to bring his team and guest to safety. Hear more from this insightful episode with Michael to learn how you can lead your team with trust and communication.

—

Listen to the podcast here

Establishing Teamwork With Trust And Communication With Michael Hingson

[00:01:13] Welcome back, my wonderful audience. We’re having a great time. I appreciate you all the time. I appreciate the fact that you read, email me at [email protected], comment on LinkedIn, and tell me what you like, what you don’t like, and what you want to hear. I’ve had some great guests in the past and done some insightful things, but this is one that I’ve wanted to get going for a while. I tried to get this person on September 11th, 2001. It didn’t happen.

Let me take you back to that day years ago at 8:45 AM in New York City and the North Tower. The plane hits 150 feet 15 stories over this person’s head. There’s chaos, heat, smoke, yelling, and panic. There’s one more thing. My guest has been blind since birth. Michael Hingson, welcome to the show. I want to talk to you without trust and communication. There is no teamwork. I’m glad to be able to have this conversation with you, Michael. Let’s get into it.

Without trust and communication, there is no teamwork. Share on X[00:02:26] One of the things I love to say is that I’ve learned more from eight guide dogs about trust, teamwork, and management style than I’ve ever learned from all the experts in management theory and so on in the world because with a guide dog, it’s all about building a team. I’ve been using guide dogs since 1964. It’s all about building a team. It’s all about creating trust and doing it with someone who speaks a different language and thinks differently than you.

If you can do that and create that relationship, you certainly ought to be able to create it with humans. The big problem with humans is that we always keep thinking, “What’s their real agenda? How do I know I can trust them?” Dogs don’t do that. They don’t trust unconditionally. They may love unconditionally, but they don’t trust. You still have to earn trust.

[00:03:13] That’s so important. It’s for us to be able to realize that trust is something that’s not automatic. I was always taught, “Trust and verify. Trust people when you have to verify that trust because if you don’t verify that trust, it can lead to some serious problems.” Michael, why don’t I let you take people back to that day and give them a little bit of insight because you are one of the 15,000 or 14,000 people depending on the numbers they’re picking that made it out of the towers? Give some people some insights into that and what you learned from that experience, and then let’s get into how that relates to trust and communication.

[00:03:53] Let’s start with a couple of ground rules. You need to understand blindness because everybody says, “It’s amazing how you got out of this because you couldn’t see what you were doing.” Blindness is not the problem I face. The problem I face consists of the misconceptions and lack of education that people have about blindness.

The fact of the matter is that a blind person can do anything that a sighted person can do. I travel and speak all over the world. If any of your readers out there need a speaker, I would love to chat with you about it. When I go and speak, especially with kids, one of the questions that I ask before even doing the speech is, “Tell me something that a blind person can’t do.” What do you think the first answer is?

[00:04:39] See.

[00:04:42] The dictionary defines to see as to perceive. That doesn’t work, either. You’re assuming it has to be with the eyes. Tell me something else that you think a blind person can’t do.

[00:04:53] I don’t know because I’ve known you, Hoby Wedler, and a bunch of blind people. I’m the worst person to be asked this because I believe that a blind person can do almost anything, if not everything, that a sighted person can do, maybe save driving a car.

[00:05:10] That’s exactly what people say. The answer is you’re wrong. If you go to www.BlindDriverChallenge.org, you will see a video on that page of a gentleman who is blindly driving a car around the Daytona Speedway right before the Rolex 24 race in 2011. Mark Riccobono is driving through an obstacle course, passing a vehicle, and doing all sorts of things because the National Federation of the Blind challenged the world, colleges, universities, and private industries to develop a car a blind person could drive.

Some people did it by using radar, sonar technology, and so on. They developed a mechanism to transmit to a driver the information that they need to drive safely down the road. Is it ready for prime time? It’s not. I’m not talking about an autonomous vehicle. I’m talking about getting the information and steering the car as anyone else would.

If you go to BlindDriverChallenge.org, you can see a video of him doing that. A blind man set the world’s speed record for a blind person driving a vehicle. He went 211 miles an hour. It was across an area. It wasn’t on the Salt Flats. It was in Texas or New Mexico. I can’t remember which. He drove 211 miles an hour and broke the record by 10 miles an hour.

The fact of the matter is blindness isn’t the problem. It is what people think about it that causes us to have an unemployment rate among employable blind people of about 65%. It’s not because we can’t work. It’s because people think we can’t work. They find all sorts of reasons not to hire us, but the reality is if they would, they would get a lot more loyal employees.

Blindness isn't the problem. It is what people think about it that causes us to have an unemployment rate among employable blind people of about 65%. Share on XHaving set that rule, I wanted to bring that discussion because when I was working in the World Trade Center, I was hired to be the Mid-Atlantic Region Sales Manager for Quantum Corporation, a company at the time that made backup products. We made the tape backup products that people use to attach to their networks and back up all of their computer data. In New York, you have to do that if you’re a Wall Street firm, for example, and keep the data offsite for seven years. We sold the equipment and manufactured the equipment that people used to do.

I was hired to open an office, set up a team, and also work with reseller partners. I did all of that. One of the things I did when I started working there was I realized that if I was going to truly be a manager and be able to do what any manager would do, I needed to make sure I could do all the things that a manager could do. For example, if we had people in, that meant taking them out to lunch. There was nowhere to go. Get to the restaurant.

I had to be able to talk intelligently about the products and all the technical aspects of it, being technical with a Master’s degree in Physics. Those are all things I learned. Especially in dealing with the World Trade Center, I learned how to find anything in the complex that I needed to find. I learned what all the little kiosks were down in the shopping area on the first floor of the shopping mall.

I learned where various offices were. I consulted with the Port Authority Police, fire prevention people, and so on, and learned what to do in an emergency. Why did I do all that? It’s because I knew if there were ever an emergency where I was going to have to be the leader to get people in my office out and if we had guests to get them out. All you sighted people look at signs. You don’t know in an emergency if the room might be filled with smoke. You’re not going to be able to see the signs.

It’s what I would do as a blind person to make sure that I knew everything that I needed to know to function properly. I want to make it clear. I needed to know that, not the dog. A guide dog’s job is to make sure that I walk safely, not to know where I want to go and how to get there, which is also another way of saying, “Dogs don’t lead blind people,” which is something that people always say to me, “Your dog led you out.”

That’s wrong. The dog did not lead me out. I gave the dog directions to where I wanted the dog to turn and what I wanted the dog to do. The dog made sure that we walked safely. It’s my responsibility to be the team leader and, in the case of a guide dog, to gain and create a level of trust, which I did. Having described all of that and set that as a background, on September 11th, 2001, we were in our office. We had some guests in because we were starting to do some seminars that day to teach some of our reseller partners how to sell our products.

We were getting pretty much to the point where we were going to do the actual seminars, but then suddenly, we heard a muffled explosion. The building shuttered. It began to tip. The building tipped. It’s a big spring. Tall buildings like that are flexible. They’re made to flex in wind and even be hit by an airplane, but nobody ever thought that somebody would hit a building with an airplane full of 26,000 pounds of jet fuel.

[00:10:23] The thing is, those planes were designed to withstand a 707, not a 757.

[00:10:30] It wasn’t the plane, though.

[00:10:31] I was the jet fuel, but it’s that much more jet fuel because it’s exponential.

[00:10:36] If the plane had hit the building and it didn’t have much fuel, the buildings wouldn’t have collapsed. The problem is that the people who hijacked the aircraft flew a fully loaded aircraft into the buildings. That destroyed the infrastructure. The bottom line is what happened has happened. For me, as soon as the building stopped moving, the mindset kicked in. I didn’t even realize I had developed a mindset that said, “If there’s something that happens, you know what to do.”

Somebody in the office with me saw fire and smoke above us and said the building was on fire and that we had to get out. I kept saying, “Slow down.” Finally, he said, “You don’t understand. You can’t see it.” The problem wasn’t what I didn’t understand and what I couldn’t see. The problem was what he wasn’t observing. What he wasn’t observing that I was, was that next to me, I had a dog who was sitting there, wagging her tail, yawning, and going, “Who woke me up?” not giving any evidence of fear at all.

Dogs have a heightened sense of those kinds of things. If the dog had sensed anything that would have caused concern, she would have been behaving a whole lot differently than she did, but Roselle was very calm. That told me whatever was going on wasn’t such an imminent threat to us that we couldn’t try to evacuate in an orderly way. Did we know what happened? No. Did I know what happened? No. Did other people in the building around us know what happened? No.

Eyesight had nothing to do with it. Reporters are always saying to me, “You didn’t know because you couldn’t see it.” Excuse me. The airplane hit eighteen floors above us on the other side of the building. Nobody knew. All we knew was we did need to get out. We got our guests to the stairs. We went to the stairs and started down. We figured out an airplane hit the building because I smelled burning jet fuel.

I traveled through a lot of airports. Back then, even for my company, I did a lot of travel. I recognized the odor, but it took me a few floors to recognize it. When I observed it to other people, they said, “We must have been hit by an airplane. That’s burning jet fuel. What happened?” Nobody knew. We didn’t know until we got out. I didn’t know what had happened until both towers collapsed.

I was able to reach my wife on the phone. She’s the one who told us how two aircraft crashed into the towers, one into the Pentagon, and a fourth was still missing over Pennsylvania when I spoke with her. We went down the stairs. We all worked together to get out. We made sure that people didn’t panic. There were a couple of times when people almost lost it. We stopped, had a group hug on the stairs, and said, “Come on. We can keep going.” We made it down to the bottom and finally made it out.

[00:13:09] The thought process is you were prepared for imminent danger long before there was imminent danger. You had the presence as a leader to sit there and say, “If there is ever a problem or a situation,” and you had no idea what it was going to be, “What do I need to do as a leader to make sure that I not only take care of myself but take care of the people around me?”

[00:13:33] That’s the point. It was, for me, also an issue. As the leader, not only did I need to know what to do in an emergency, but I needed to know it so that if, for example, we had customers coming to visit us. My sales staff brought somebody in. We did a demo. We were going to go to lunch, come back, and discuss contracts and pricing.

I needed to take charge as any leader would do because how would it look if I said, “I don’t know how to get anywhere. I’m going to have to hold somebody’s arm and be taken to wherever we’re going.” Who’s going to want to negotiate with me? I needed to negotiate and be able to be viewed as somebody who could negotiate from the power of strength or at least conviction that I had. I needed to be able to function as well as anyone else who had the same job that I had.

[00:14:24] I don’t disagree with that. I probably had a far better view of what was going on in 9/11 than you did because I was sitting 3,000 miles away with 40 cameras from 25 different angles pointed at this thing with running commentary about what was happening. The people that I know that descended through the tower tell a similar story that you did. They didn’t realize until they got out the extent of the impact and the danger of what was going on until they were out of the building.

It came down to how some people led and some people followed. A lot of it had nothing to do with the title on your business card. It had to do with your sense of presence and your ability to communicate, build trust, and develop the teamwork necessary to get your team, and that team included the guests that were on your floor that day, down to safety.

[00:15:16] It’s all about having the presence, the conviction, and the understanding of what was involved in leading an office in that complex. I believe that anyone who is going to be a leader should do the same sorts of things that I did. Don’t rely on signs. You need to take charge of what you’re doing. The other side of it is that you never know who’s going to be a leader at any given time. It doesn’t matter what’s on your business card.

The fact is that some of the people who helped lead that day, and some people who took a leadership position even for a few moments, did so because they were in the right place at the right time and took charge. When somebody else could do a little bit more than they did, then leadership was relinquished or shared, which is just as important. That’s also true on the job.

The reality is the boss may not be the leader. The boss may not be a good boss if the boss doesn’t know that the boss isn’t necessarily the leader. The reality is that all of us can and should be leaders where we can do the best job to make our options what they need to be and make the company more successful. The heads of companies need to recognize that all the more now than ever.

[00:16:36] Let’s bring this down back to the here and now years ago. What did you do? Were you the senior person on the floor at that time? Were you the person that was “in charge” if you want to take a look at business cards?

[00:16:49] In that office and for my company, I was the guy. I was a Mid-Atlantic Region Sales Manager. I hired sales staff and was involved in hiring our support staff and others.

[00:17:03] I have no idea how many people were on that floor that day, but I’m assuming it was not ten people. How did you go about being able in the middle of the chaos to have the presence of mind, gather people, and move them quickly, efficiently, and effectively to the exits? Take me back a month, a year, or five years ahead of time. What are the things that you built within you that enabled you to have the respect of the people where they trusted someone who was not sighted to be able to take charge and move everybody forward at that point in time?

[00:18:01] Our office wasn’t the entire floor. It was only part of the floor, but we did have 7 or 8 people in our office. Your question is still valid, not only for the office but for going down the stairs. Let me answer it this way. My parents brought me up to recognize and believe I could do whatever I chose to do. In reality, there were risk-takers because they let me do that. I became somewhat of a risk-taker. I tend to be pretty outgoing, especially in situations where I want to get more information or be able to use the information that I have. I need to do that not in an arrogant way, but I need to do it in a way that builds a relationship.

When we were going down the stairs, there were times when I knew there were a lot of people following me down the stairs. I know it because people told me about it later, but at the time, what I was doing was trying to not only keep myself calm by focusing and not worrying about the things that I had no control over but also, I had an instantaneous and immediate responsibility to keep a dog focused. Roselle, my guide dog, would certainly become more nervous and tense. She sensed fear all around us, especially if she sensed that I was afraid.

I didn’t dare show fear while working with her because that would have affected her ability and her actions as a guide dog. I needed to be able to focus. I did so by saying things to her all the way down the stairs, “Good girl. What a good dog. Keep going. What a good job you’re doing. Good dog, Roselle.” I was doing that all the way down the stairs, but what that did was it also was something that other people were observing. They told me, “You were calm all the way down the stairs. If you could be that calm going down the stairs, then we’re going to follow you down the stairs.”

Those are the kinds of things that happened. For me, being blind, I recognize that I need to be confident in what I can do. I also need to recognize that I need to learn all the time. There are always going to be new things to learn. I’m not going to sit here and say, “I know everything there is to know.” I will always say, “I want to learn more,” but I will use effectively the knowledge that I have in dealing with September 11th, 2001 and developing a relationship with people.

In my office, for example, whenever I hired someone, one of the things that I said to them was, “I hired you. I’m your boss, but I hired you because I believe you know how to do what it is that you need to do. Your job and my job together need to be however to figure out how I can add value to you to enhance you and help you do your job better. My job is not to tell you what to do, but I do want to add value and help you be more successful.” The better salespeople I hired got that.

We found ways to work together, go into meetings, double-team the people in meetings, do all sorts of things that were very effective, and also help to develop a level of trust not only between ourselves but with the people that we were meeting with. For example, if we went into a sales meeting somewhere at Salomon Brothers at the time where we were going to be discussing our products and doing a PowerPoint show, I did the PowerPoint show because they wouldn’t expect that. I was able to keep their attention.

Help develop a level of trust, not only between us ourselves, but with the people that we were meeting with. Share on XOne guy came up once after doing one of those presentations and said, “These shows are usually pretty boring. Yours wasn’t. We didn’t dare fall asleep as we usually do because you also didn’t turn away, look at the screen, and pointed things.” I practiced doing the show, so I pointed over my shoulder, “You didn’t look away. We forgot you were blind. We were afraid that if we fell asleep, you would catch us.” I said, “If you remembered I was blind, it wouldn’t have mattered because the dog is down here taking notes. We would have got you anyway.”

The point is that you use the skills that you have, but you have to use them in a way to earn respect and establish a relationship. In the meeting that I mentioned, by the time we were done, because I kept asking questions about what they were looking for, our product wasn’t going to do what they wanted. I told them that. I said, “Here’s why it won’t. Here’s another product that will. Here’s why it will.” They bought that other product, but two weeks later, they called and said, “We’ve got another project. It’s bigger than the first one. We know because of everything that you taught us and we trust you that your product is going to do what we need. Tell us the price. We will order it.” That’s trust.

[00:22:35] That’s huge trust. There’s so much to unpack there. The first thing I think about when you’re dealing with your salespeople and the rest of your teams is expectations and accountability, whether you’re blind, whether you’re sighted, whether you’re in a wheelchair, or whatever you are. It comes down to if we set expectations and communicate what we need from each other, not just you with the team members but the team members with you.

You hold each other accountable. It’s amazing the things that could happen because salespeople need to know, “When I come to Michael and I’ve got a real problem, Michael is not going to ignore me.” You need to know that when you give people a task, they’re going to figure out a way to make it happen.

[00:23:16] They’re going to ask me for help to make it happen. That’s what a team is all about. Accountability is key. There’s nothing wrong with an employee holding a boss accountable. That is important for me to be able to say, “Here’s what I commit to doing.” You certainly have the right to ask how it’s going because it may very well be that I got stuck, and you can help me move through it. That’s how we work together, but accountability always goes. It isn’t just the boss telling subordinates what to do in a real team that’s working well together.

[00:23:55] The other part you’re dealing with in customer relationships is that when you create the unexpected for them or when you give them something to think about that’s beyond the normal, different, and unique, you become memorable. If everybody can sit there and say, “I’ve got strengths. You have strengths. I have weaknesses. You have weaknesses. Let’s play to both of our strengths.”

“Michael, you do the presentation because it’s going to be coming in a way that they weren’t expecting. You’re qualified to do it. We’re going to get their attention far better in this particular case.” It’s a matter of sitting there and going, “It’s not about my ego versus your ego.” It’s saying, “What’s the end objective? What are we trying to achieve? How do we work as a team to be able to get there?”

[00:24:42] A number of my employees at various times said, “How come you know so much about all this? How come you’re able to do this? How come you know so much technical about the products, and I don’t?” Even my best sales guy asked me this when we went to one of our meetings, “How come you know all this stuff?” I said, “Did you read the product bulletin that came out or the product briefing?” He said, “No. I’ve been pretty busy.” I said, “There you go.” They’re not put out just to put them out. They’re put out for information. We all need to make sure that we keep up with that stuff.

That’s part of what we need to do to be as competent as we can. Admittedly, I tend to be more technical. I’ve always been. I would probably pay a lot more attention than most salespeople would to a lot of the products, things, and updates and know more about the products and all that. That gives me value-add for them. I knew that they weren’t going to spend all the time that they could or probably should reading all the technical stuff, nor would they get it all. That’s okay as long as the knowledge is available and they use it. If that means letting me help, then that adds value to them, which is great.

[00:25:56] It’s also about fostering curiosity. Something that we as a society are losing is the ability to be curious to ask, “Why? Why not? How come?” and be looking for more information to not take everything for granted, not to say, “I assume it’s going to be this way. Therefore, it’s going to be this way.” I’m assuming that a blind person couldn’t drive a car. That’s an assumption I’ve had my entire life.

If that can change, if the technology ever becomes available that allows for that hand-eye coordination or lack of hand-eye coordination and the response time and be able to have the technology that can be able to mitigate it, that’s phenomenal, but I hadn’t even thought that it was even a possibility. It’s amazing when you sit there and say, “Let’s forget about our assumptions and what we think we know and find out if something is true or not true.” We put ourselves in a far better location.

[00:26:53] Going back to blindness and disabilities in general, the average employer thinks it costs a lot of money to provide accommodations to make it possible for, let’s say, a blind person to work at your company, “You need a special software so that your computer can talk. You need one thing or another.” Let’s look at what happens in the average company. They spend hundreds or thousands of dollars providing nice and fancy touchscreen coffee machines, which also are inaccessible.

People can get hot chocolate, all different kinds of coffee, tea, and all that. They have lights so that you can see to get around in the building. You’re provided with a computer and a monitor so that you can see what’s going on with the computer. You’re provided with a desk and a chair. Those are all accommodations that employers provide.

Why should it be any different instead of providing me with a monitor? Instead, provide me with software that allows me to hear what’s coming across the computer screen or perhaps someone to read the information that is otherwise visually inaccessible. Why should that be any different than providing some of the frivolous or maybe not-so-frivolous but still not as necessary as we think they are accommodations that we already provide for people?

The fact of the matter is that the upside of providing me with what I need to be able to be employed by your company is greater than what would happen to be the case for the average employee because I know and many of us who are blind, for example, know how hard it is to get a job. We know how hard it is to crash through that barrier that you have around you of what it’s like to be blind because you don’t know.

People make assumptions, but if you hire me, there is a significantly greater chance I’m going to want to stay with you because I don’t want to go off, try to do another job search, and go through all that again. I don’t want to go through all of that. I’m going to stay where somebody appreciates me and where they have demonstrated their loyalty to be. There are a lot of statistics to show that. Providing me with the appropriate accommodations is no different than providing anyone else with accommodations. It’s specifically a little bit different thing. It isn’t more expensive. It is an expense that’s part of the cost of doing business or ought to be.

Providing a person with a disability isn't more expensive; it is just an expense that's part of the cost of doing business, or ought to be. Share on X[00:29:24] I agree with you, but the challenge is, and I’m going to take this from an employer or a small business point of view, we don’t know what we don’t know. We don’t know how much it’s going to cost, what accommodations we need to make, or how we access government funding.

[00:29:39] You’re worried about that. Why do you even think about what’s the cost of hiring a blind person as opposed to hiring a sighted person? Why do you even make that differentiation? Why don’t you say, “What is the cost of doing business?” Rather than making the assumption, why don’t you, for example, ask me what you are going to need? We have a budget for bringing on employees. We will use areas of that budget. I’m willing to put a little bit more money into it, but why worry about it in terms of numbers?

Ask me what I need and how to get there because, in part, my job as an employee wanting to come into your company should be to help educate you. The answer to the question of the cost is there are a number of different kinds of programs. All states have a department of rehabilitation in the United States. There are similar things in Canada. Organizations like the Canadian National Institute for the Blind can help. There are a lot of resources.

The fact is, as an employee wanting to join your company, I need to be the expert to help you with that because if you let me do that, you’re willing to be wise enough to ask me those questions, and if I have those answers, that should convey something to you about how thorough I’ll be for your company, but more importantly, I can then give you and help you get the information to make it possible for you to want to hire me and spend whatever money you need to do.

It comes down to, “Don’t make the assumptions,” as you pointed out, but rather be more open to asking me because, as the employee, I better have those answers. Otherwise, why would you want to even consider me it? That’s true for any employee that you hire, but typically, for most employees, it’s a standard thing like a monitor computer, access to the coffee machine, and so on. I happen to be different because I’m blind. Some of that’s going to be different. Who should be the person to best guide you as an employer through that process? It should be me.

[00:31:50] A lot of it comes down to perception, “This is going to be an exorbitant cost,” which it probably isn’t. It’s perception. It’s not knowing what you don’t know.

[00:32:02] Go back and take the leap the other way. It costs $2,000 more because you have to buy a special software package from me. It isn’t $2,000. It’s less than that, but I’m just making up a number. I want to make up a decent number of $2,000. The question you’ve got to look at also is, “What is the benefit of me hiring you?”

[00:32:25] The long-term ROI is proven. There’s no question that the long-term ROI is proven. The more loyal employees, the more engaged employees. Employees have longer tenure. There’s no question about that. The problem comes down to people don’t know what they don’t know. If employers took the time to educate themselves to be curious, learn, and communicate, they would find that it is not as big and onerous a challenge as they think it is. That’s where we need to take and leave this conversation. The opportunities are there. People of all different abilities can make phenomenal employees. It’s a matter of giving them the opportunity to prove themselves. They deserve it.

[00:33:14] I use a piece of software called JAWS, which stands for Job Access with speech, which is a software package that will monitor what’s going to the video card on my computer and then, as a result, to the monitor. It will verbalize it if it’s text. There’s a cost for that, but I have a copy of it because I use it at home. The issue is I would say if somebody were going to be hiring me, “I can bring JAWS in and install it.”

“We need to have our copy because of security and all that. That means you’re going to have to pay for it,” or we explore the United States, in my case, the California Department of Rehabilitation that wants me to be employed providing that product. Some companies might say, “Bring your own in,” but it depends on the company. Don’t ding me if you decide you don’t want me to use my software.

Don’t hold me responsible and say, “It’s more expensive.” I can appreciate that. A lot of people have computer monitors. You don’t see them offering to bring their monitors in because companies provide them. It should be as automatic to make accommodations for a person who happens to have a disability. It’s a reasonable thing to expect.

Most people don’t know it and make the wrong assumptions, but that is what we do in general anyway. We don’t understand this whole idea of disability. I wish there were a better term. Disability doesn’t mean a lack of ability. Disability is a categorization only for the purpose of saying, “I happen to be a little bit different than you, but don’t assume from it that I’m incapable.”

Disability doesn't mean a lack of ability. Disability is a categorization only to say, 'I happen to be a little bit different than you.' But don't assume that I'm incapable. Share on XI’ve had job interviews canceled when I didn’t say in advance that I was blind. I had a headhunter who wanted to see my resume. They knew I was looking for a job. They loved the resume. They had a company that wanted to look at me, interview me, and so on. We had an interview set up. We even had airplane reservations made. They bought a ticket.

The night before, the headhunter called and said, “I was looking at your resume. I see that you do a lot of stuff with blind people. Is somebody blind in your family?” I said, “I am.” The interview was canceled. It didn’t matter what was on the resume. We didn’t even get to costs or anything, “You’re blind. The company is not going to want to talk to you then.”

“Why? You saw my resume. You liked my resume.” “That doesn’t matter. You’re blind.” We’ve got to get over that concept. It is unacceptable. There are laws. They’re not as strong in Canada as in the US, but the laws are there. The reality is that society is much slower than with other minorities, but it is slowly recognizing that the so-called disability isn’t the problem. It’s our attitude.

[00:36:03] There’s no question we could talk about this for hours, but I need to land this plane figuratively and metaphorically. What’s the best way for people to get in touch with you? You’ve got so much information to give people. People need to hear from you. What’s the best way for people to get in touch with you so they can get the information directly from you?

[00:36:21] They’re welcome to go to my website, www.MichaelHingson.com. There’s a contact form if they might want a speaker to come and speak to a company or a sales meeting. I’m always looking for those opportunities. I’m glad to consult and help companies understand and work with them, not only about disabilities but building teams. I do that. We didn’t mention it, but I work for a company called accessiBe that manufactures products and help make internet websites more accessible.

You talked about assumptions. The problem in the world is that over 98% of all websites have not done anything to specifically put the appropriate coding, procedures, and processes on their sites to make them accessible. With so many websites being created 180 a minute, we are seeing an increasing gap of websites that aren’t accessible, ironically, when every website could easily be accessible.

[00:37:26] Let me ask you one last question and then let you out the door. The question I ask everybody is this. When you leave the meeting and head for home, what’s the one thing you want people to think about you when you’re not in the room?

[00:37:38] It’s that they can trust me and that I will do all I can to assist and be a value-add to them and whatever they do.

[00:37:48] Michael, thank you very much for telling your story. Thanks for being such an amazing guest. People need to find out about accessibility. People need to find out how to be able to hire blind people and people with accessibility issues and realize that they add as much value as everybody else. We need to find ways to be able to sit there and say, “How do we work differently to be able to make sure that these people can add value to our organization?” Thanks for being with us.

[00:38:16] Thank you.

Important Links

- [email protected]

- Michael Hingson

- Blind Driver Challenge

- National Federation of the Blind

- Canadian National Institute for the Blind

- JAWS

- California Department of Rehabilitation

- accessiBe

- Facebook – Michael Hingson

- Twitter – Michael Hingson

- YouTube – Michael Hingson

- LinkedIn – Michael Hingson

About Michael Hingson

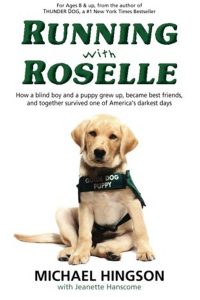

Michael Hingson is a #1 New York Times best-selling author and international lecturer.

Michael Hingson is a #1 New York Times best-selling author and international lecturer.

Michael, blind since birth, survived the 9/11 attacks with the help of his guide dog Roselle. This story of Teamwork and his indomitable will to live and thrive is the subject of his best-selling book, Thunder Dog. Hingson gives hundreds of presentations around the world each year speaking to influential groups such as Exxon Mobile, AT&T, Federal Express, Scripps College, Rutgers University, Children’s Hospital, and the American Red Cross to name a few.

“Thank you for the great session with the Hartz employees. You have motivated everyone by showing that life is a series of choices.”

— Robert Devine, President, Hartz Mountain Corporation

Hingson is an Ambassador for the National Braille Literacy Campaign for the National Federation of the Blind and also serves as Ambassador for the American Humane Association’s 2012 Hero Dog Awards. In countless TV and radio appearances, feature articles, and speaking engagements, Hingson does much more than simply tell his own 9-11 story; he continuously explores the broader lessons of his life and experiences.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share! https://yourbrandmarketing.com/yourlivingbrand-live-show/