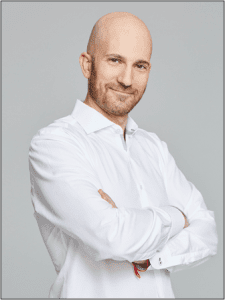

Recent years have shown a rise of on-demand workers, with the current pandemic only accelerating the growth of what is now called the gig economy. Joining Ben Baker today is Jeff Wald, Co-Founder of WorkMarket, an enterprise software platform that enables companies to manage freelancers. Jeff is a serial entrepreneur, an active angel investor, startup advisor, and serving on numerous public and private Boards of Directors. In this episode, he expounds on insights from his book, The End of Jobs: The Rise of On-Demand Workers and Agile Corporations. Jeff also shares crucial tips on how workers and employers can adapt to this change with transparency and authenticity. Tune in to learn more.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

The End Of Jobs And The Rise Of On-Demand Workers With Jeff Wald

[00:01:21] We’re talking a lot about the gig economy. We’ve been talking a lot about where is the future of work? Where are things going? A lot of businesses, large and small, are scratching their head going, “Post-COVID, where we are.” My thought process is, “This goes way beyond COVID.” The future of work happened long before COVID started. COVID might have been the accelerator but there’s some real good conversations about where the world is going and how we have to adapt in order to be relevant. I’m bringing Jeff Wald to the table. Jeff is the author of a book, The End of Jobs: The Rise of On-Demand Workers and Agile Corporations. Jeff, welcome to the show.

[00:02:05] Thank you so much for having me. It’s great to be here.

[00:02:08] A quick shout-out to Mark Hershberg, who I had on the show. Mark said, “Ben, you have to have Jeff on the show.” He was adamant about it. He said, “You have to hear Jeff’s story. You have to hear the things that he talks about.” I’ve been to your website and I watched your videos. He is correct so I am looking forward to this conversation.

[00:02:29] He has been more effective than my PR people, and I appreciate that. They may well read this so they should know that my friend, Mark, who is amazing, has been a wonderful advocate.

[00:02:40] We all need people like that. We all need people who can just sit there and go, “This guy is amazing. You need to talk to him.” We all have those people in our lives or hopefully we have those people in our lives. Those people should be treated like gold because that’s what they’re worth. Tell me a little bit of a history of Jeff. You are a serial entrepreneur. You’ve been in this game a long time. Give us a little history about where you came from and what brought you to the table.

[00:03:08] I grew up in upper-middle-class America, a little town called Port Washington, suburban New York City. Honestly, it’s like a Norman Rockwell painting. It’s suburbia USA. I was unbelievably fortunate to grow up there with my family. I started my career not in an entrepreneurial way. It’s not like, when I was a kid, I had lemonade stands, a business shoveling sidewalks and things like that. I didn’t.

I started in a very traditional route, which was investment banking. I was an M&A banker at JP Morgan. I left there to work in a venture capital firm backing entrepreneurs and it was there that I got this taste for, “There’s a group of people out there that want to start an entirely new way of doing x.” If they succeed, they’re going to make a ton of money. If they fail, they’re going to dust themselves off, keep going and they’re going to try something else.

I left that venture firm and I started my first company. It failed miserably. It left me broke. I got the call from my mom, “Do you need to move back home?” That’s a wonderful call to be able to get, to be able to have that support system but just because it’s a beautiful thing doesn’t make it any less horrifying to get that phone call. It didn’t come to that but I won’t pretend that I was so quick to pick myself up and dust myself off. It took some time to lick my wounds and to deal with that failure but I did and started another company. That company eventually got sold to Salesforce and so that was a good outcome.

The most recent company was WorkMarket, where we were helping companies all over the world to organize, manage and pay their freelance workforce, their on-demand workers. Our software was this enterprise software platform that helped efficiently and compliantly engage this very important and growing segment of the labor force.

We raised about $100 million from SoftBank, Union Square Ventures and others. We sold the company in 2018 to ADP, which is just this amazing company. People think of them as this payroll company and they are the world’s largest payroll company but they’re also the world’s largest HR software company. They wanted to bolt WorkMarket onto all of their full-time software programs. It has been amazing and it gave me the space to finally finish this book that I’ve been working on for about five years before the acquisition.

[00:05:35] That is an amazing journey and the fact that it’s the lessons that you learned along the way. My question to you is what were the lessons that you learned in your previous entrepreneurial experiences that led you to WorkMarket, that led you to the a-ha moment that the gig economy needs help? That’s the crux because it does. A lot of it is ad hoc. A lot of it happens in the shadows. A lot of it happens by accident. The question is how did you have that a-ha moment that you said, “This is a part of the workforce that needs to be organized and helped to be able to make it legitimate in the world.”

[00:06:24] I’m not an a-ha guy. I’m not a guy that’s like, “I got it.” That’s not Jeff Wald. Jeff Wald is, “I have some data here. I’m going to analyze it. I’m going to talk to a bunch of people smarter than me. I’m going to let them challenge it. I’m going to get more data and I’m going to put together a plan.” If I think that thing has a high probability of working, I’m going to execute that plan. There was no one moment.

That said, I started working on the concept that is WorkMarket years before. Every time I make an angel investment or I talk to start-up founders, I’ll always start with this question, “What is the problem you’re looking to solve? Whose problem is it? How big of a problem is it for them? How big of a problem is it for the economy?” As an investor, I want to back people that are solving big problems. The bigger the problem you’re trying to solve, the more likely you are to be able to make a living or build a company solving it. If you’re solving a very small problem then good for you and for the people that it’s their problem but you’ll have a low probability building a company investor is going to make some money on.

It’s something I always thought about. As I was thinking about WorkMarket, I remember reading a study by McKinsey, not the dumbest people out there, about the on-demand economy in corporations around the world. This study was in 2006 or 2007. It talks about how there was about $1 trillion spent in on-demand labor the world over but companies lack the systems and processes to manage it efficiently and compliantly. If companies had the right tools, that $1 trillion could become $4 trillion. I remember thinking, “That’s a big problem to solve. Let’s get companies these tools. What do those tools look like?”

Let’s look at the dates here. That was 2006, maybe 2007. I didn’t start WorkMarket until 2010. There were a lot of conversations. There was a lot of debate and discussion. There was a lot of whiteboarding and putting together presentations and then letting people challenge that notion of what was it going to take to solve it, to drive that kind of growth. I don’t think we hit it perfectly but we did well enough. ADP now is a great home for WorkMarket and they’re doing a wonderful job with that technology and with that team.

[00:08:52] You said this is a 2006 ideation of, “Maybe there’s a problem.” The actual company started in 2010 but there was this little thing called the 2008 crash that came right in the middle of that. I was fortunate to start my company on January 5th, 2008. I left my partner and went out on my own on January 5, 2008. Thank God for good customers that carried me, that took care of me, that allowed me to be able to do that because I took care of them.

The bigger the problem you're trying to solve, the more likely you are to be able to make a living or build a company solving it. Share on XI remember watching this in one of your videos. There used to be the fact that when we have a down economy, you let people go. As the economy increases, as it becomes better, you’re not willing to risk having full-time employees yet so you hire people part-time. You hire them on a gig basis. You hire them as you needed and then you convert them to a full-time basis. You said in your video that 2008 was a watershed moment because people did not convert those people. The question is why. At this point in time, why was there not the conversion? What was the catalyst that people said, “We don’t have to have another 40,000 people, 20,000 people, 5,500 people on payroll. We can do it in a different way.”

[00:10:15] This decoupling from the countercyclical trends, like when the economy is good, the gig economy would do poorly. When the economy is bad or starting to recover, the gig economy does well. This was countercyclical to the economic cycle. It decoupled beginning in 2008 but we see it in the data around 2010,2011 as the recovery takes hold. The economic recovery from the Great Recession was very slow. It took us until 2011 to start seeing in the data that the gig economy wasn’t decreasing and it continued to grow.

There were a host of reasons. One was a psychographic change that workers all of a sudden said, “I’m okay being on demand.” Whereas before, workers were very focused on, “I want to get that full-time job.” Some of that had to do with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Suddenly, I was able to decouple my health care from work. I knew now I could go into these exchanges and I could get healthcare. It may not be the best plan. It may not be this, that and the other thing. I’m certainly not here to debate that but there was an understood option that suddenly tens of millions of people were taking.

That allowed for some decoupling and the psychographic shift. If I were to ask somebody in 2007, “What is the word that comes to mind when you say freelancer?” The number one associated word at the time was unemployed. “You’re a freelancer. That’s adorable. You’re unemployed. Go get a job.” If you ask people now, “What is the number one word associated with freelancer?” Do you know what they say? Entrepreneur. It’s a huge change.

We have the psychographic shift. It was driven by a host of things, including healthcare but we also had system shifts. WorkMarket was coming on stream. Not that we were big enough in 2010 as we were just starting to impact this but there was another category of software called VMS, Vendor Management Systems, that help companies manage their temps. The largest of the list are Fieldglass, IQNavigator, Beeline, a host of others. They were coming on stream.

The point being, one of the reasons that you converted people from a temp, freelance or other gig workers into a full-time worker is because you didn’t have the systems to manage them as temps and freelancers. You’d look around going, “Who are all these people?” We need to get them into our payroll existence and our ADP HR systems so we know who they are and what they’re doing and we can have better control, understanding and insight into our workforce. When they’re gig, somebody is managing them off a spreadsheet.

With VMS software and WorkMarket creating the category of FMS software, Freelance Management System, you suddenly had the systems to manage them efficiently and compliantly. Working in HR, legal and procurement, you don’t feel the need to say, “Convert all these people to full-time because we don’t know who they are.” We had a psychographic change and we had a system change that both led to that decoupling.

[00:13:44] You had a technology change in terms of laptops were faster. Smartphones were coming on to the market. Internet speeds were becoming a point where you could have live conversations across the internet, the novelty of Skype to be able to have video chat and all those types of things, where it enabled workers to be remote and log into systems and be able to log into networks in a way that they never could before because there wasn’t the technology. I’m sure there was a myriad of different things that allowed that to happen.

[00:14:24] Technological changes enabled this breaking of the bone. When I called the book, The End of Jobs, it’s not to say that I think jobs are going. The conclusion of the book is quite the opposite, that robots and AI will have no net impact on the number of jobs in society and net being the important word there. When I talked about the end of jobs, I was talking about the end of the 9:00 to 5:00, one office, one manager job. That job is going.

Technology, like all the things you highlighted, is one of many factors that help break that bone of, “We need everybody in this office from 9:00 to 5:00. They all have to be within one reporting structure and we need to understand where everybody is.” That job is dying. Technology has accelerated it, COVID has certainly accelerated it and the remote workforce and the gig workforce are all a very big component of the new world of work.

[00:15:15] When I think of all of that, the one word that comes to mind is control. It’s the ability to control because there are a lot of workforces right now that are doing whatever they can to drive the workforce back to the office. Whether this is good for the business, for the employees or for the leadership, they’re trying to bring people back to the office.

First of all, they’ve got these enormous buildings that they’re paying leases on that are sitting empty. They look at this as a cost that’s being wasted but it’s also a myriad of control. I hear stories in March of 2020 about people that were having keyboard trackers installed on all their software. The “leadership” could make sure that you were working from 9:00 in the morning until 5:00 in the afternoon. I look at it as control and trust.

My question is how do we go from a control and trust environment to one where it is expectation-based? One where we are sitting there going, “I don’t care whether you work 8 hours a day, 12 hours a day, 20 hours a day. I need you to do this task. I’m going to pay you to get this task done. When that task is done, we’re going to work on the next task.” How do we shift that mentality from a workforce point of view to make task-related workers and ideation workers instead of 9:00 to 5:00, put in your hours and I’ll pay you for the amount of time that you’re there?

[00:16:51] We could literally spend an hour responding to that. You and I can go back and forth. This is a great question. It hits on many different themes. To answer that question, we need to go back in the history of work because this is a constant tension between companies and workers. I argue in the book that we can think about the history of work and quite frankly, the future of work, as this undulating power balance between companies and workers, where companies almost always have the preponderance of power in that relationship wherein our three industrial revolutions that have occurred and we’re now in the fourth as a lot of people call it, power accumulates even more to companies.

You get these counterbalancing forces that workers argue for that are regulations, the social safety net and unions or collective associations because the union structure is evolving, that help not bring things into a balance of power, there’s never going to be balance but within some stability. Within that is the company’s inherent need to control these workers to maximize productivity. Companies have always had that. Now it’s easier to do when everyone is on a factory floor and everything is quantifiable but as you move to more knowledge work, what is productivity? I would get some sniping from people in my office because sometimes I’d come in at noon. It’s my company. I come and go as I want.

Every now and again, someone would say some snarky comment that I would overhear and I’d be like, “Let me be clear. I can pick up that phone and in twenty minutes, do what it takes you a week to do.” I’m not boasting. I’m just saying I’m very efficient because of the relationships and reputation I’ve built up. I can work when I want and how I want. I’ve earned that right.

The remote and the gig workforces are all very big components of the new world of work. Share on XDoes that make me inefficient? Does that mean I’m not as productive? No, I’m super productive but how do you measure it? Keyboard tracking and all these other things are insane but they fundamentally go to the supply and demand balance of workers. If you want to treat workers like cogs in a machine, make sure that they are very interchangeable and there’s a large supply of workers ready to fill those roles because you’re going to have people that are unhappy and they’re going to leave you as quickly as they can.

If there is a huge supply and demand the other way, think about blockchain developers, cybersecurity experts or AI experts, very STEM-oriented and technology-driven jobs, there is a massive shortage of those types of workers. A large number of those workers want to work not as a full-time worker anywhere. They work as on-demand workers. They say, “I’ll consult for you for six months and I’m going to come and go as I please.” That’s what the worker wants. The company doesn’t have a choice. They’re like, “You’re the only person that even responded to the ad. You’re the only person I could get on the phone so however you can, please, help us.” That’s how we see the extreme one way. We talked about the extreme the other way with keyboard tracking and monitoring your workers ridiculously. It differs industry by industry, job function by job function, sometimes company by company.

In this market that we have now, there are acute labor shortages. Hopefully, it’ll be temporal. If you want to be an employer of choice and I would say every employer wants to be an employer of choice, your number one asset is your people. You either attract the right people that are going to move the needle or you are getting people that are just punching the clock and want to get the heck out of there.

If you want to be an employer of choice then you want to have an effective team. The underlying variable, the most important aspect is trust. If you want to have the best and the brightest company, you got to trust them. That doesn’t mean you don’t have KPIs and you’re not managing them. You do that, but that amount of control that over time has not served companies well save for specific industries and specific functions. If you need to get a certain number of widgets out the door and it’s not happening and your processes aren’t working then change your people. I’m sorry but there are certain jobs and functions where you have no bargaining power. That is what it is.

[00:21:15] That’s true. I use the phrase all the time that your brand is only as valuable as your unhappiest employee on their worst day. If you have unhappy employees, if they don’t feel listened to understood and valued, they’re never going to represent your brand. Whether they’re gig employees or full-time employees whether they work at head office or in the branch office, it doesn’t matter.

Senior leadership down to the person on the floor, every single person represents your brand. You need to make sure that those people feel like they’re valued, that they’re part of the team, that they know their work matters to be able to move the business forward. If they don’t, they become more of a hindrance for your company than they become a help. Leaders need to understand that their role is to enable new leaders to emerge and allow other people to have the ability to grow within the company.

[00:22:20] I will agree vehemently with all of that. The only build that I’d love to do here is to say that’s not necessarily true of every single company. That’s the best way to succeed but if that’s not what’s optimal for you, be very clear about it. Don’t put on the wall, “We value the employees.” You don’t value the employees if that’s what you’re doing. You just want cogs. If that’s what you want, it’s terrible. I don’t think it’s optimal but I won’t pretend to understand every company in every industry and every job function. I don’t.

What I have found, as I’ve studied the history of work and advised companies on labor force transformation is that transparency and authenticity are very valued. “My company doesn’t care about me. They just want me to come in and do a job. I’m fine with that.” You’ll get the worker that wants that. Again, it doesn’t work for me. I wouldn’t run a team that way but if that’s who you are and that’s what works for you, be clear about it. You have a much better chance of being successful.

[00:23:18] I agree. There are certain people out there that just want to come in, do their job, get a paycheck and when they walk out the door, they’re gone. They don’t want to be invested in the company. They don’t want to go to company picnics. They don’t want to go beyond the bowling league. They don’t want to go out for drinks with people.

They want to come in, run the press, ship the stuff, be the shipper, whatever they need to do, do their job, go home to their wife and their kids and be with their friends. There’s nothing wrong with that but you need to understand both as a company and as an individual, what are people’s motivations. You need to be open, clear and honest about it. If we’re not looking for great big idea people, don’t put, “We need great big idea people,” as the first line on your ad in the newspaper. Hire the people to be part of the culture that you have, not the culture that you think everybody wants you to be.

[00:24:21] It is difficult to work at a company I run. We have bowling teams because I like that stuff. It is clear with everybody from the job posting and from the interviews what it is like to work at a company I am running. My nightmare scenario is you get there and after a month you’re like, “I don’t like it here. I’m going to quit.” We wasted all this time recruiting you then we hired you and we onboarded you and now you’re leaving. That’s a terrible scenario. I’d rather be upfront that it is a hard-charging environment.

We are here to get things done. We are not here to talk about your feelings. We are results-oriented and that’s who we are. We think we’re going to do a lot of great things and they’re going make you a lot of money but if you’re not on board, if that’s not what you want, don’t come. That’s fine. Fine for you and fine for our team. We’ve been lucky and I will take the fact that most of my employees now that they know I’m going to start another company I’ve been reaching out. I asked them to come back. I will take it as a sign that we’re doing something right.

[00:25:23] People are drawn to people. People sit there and say, “This is what I can expect from Jeff as a boss. This is exactly what I’m going to get from Jeff. I know where he stands. I know when I’m in trouble. I know when I’ve done a good job. If I do this, this is what the possible outcome is probably going to be.” That’s a great place for a lot of people to work either whether it’s from a gig point of view or a full-time employee point of view.

If people understand where they stand, what’s expected of them, what the motivations are, what the triggers for success are, what the opportunities are, they’re willing to stay. The stats have told me that every employee that leaves you costs you $100,000 to replace. Why would you want to hire somebody that months later goes, “I don’t want to be here.”

That’s probably a great thing about gig workers. You can have them work for you for six months on that gig basis and say, “You’re here temporary to do this contract. If you like it, let’s have a conversation.” The person could either continue to be a gig or you can morph them. It’s a matter of looking at the economy differently saying, “How do we make things work for everybody?” As you said, it’s that balance of power. What are the things that most companies are getting wrong? There’s got to be 1 or 2 things that most people either are not paying attention to or they’re overlooking that are going to be those little tweaks that make them go from good to great.

[00:26:58] We’re going to circle back and touch on a few things we’ve touched on but I’m going to frame them in a little bit different way. I’ve been asked, “What do we do with remote work? How do we keep a cohesive culture? How do we keep people productive?” I will start by saying, “Let’s double click on that word, culture. What does that mean to you? Do your people understand who you are, why you’re here, where you’re going and what you stand for?” Those are the big four.

If you want to be an employer of choice, then you want to have an effective team. The underlying variable, the most important aspect, is trust. Share on XWhen people say, “Culture this, culture that,” I will always say, “Do you have a culture document? Are you codified? Are you writing down on paper who you are, why you’re here, where you’re going and what you stand for, the mission, the purpose, your values? Importantly, do you then write down all the policies, procedures and behaviors that support all those things?” If you don’t do it, they’re just words on the wall.

Our friends at Enron had accountability and honesty up on their wall and you know what they were? They’re bullshit. They’re just words on a wall. They don’t mean anything. They would have been better off if up on their wall, it said, “Make money at every cost and cut every corner to make a dollar.” They might still be around, quite frankly.

[00:28:18] They wouldn’t have been crucified in the press as badly. I’ll tell you that much.

[00:28:22] This is who we are. This is what we’re doing. We are running and gunning. The culture document to me is the most important thing because it is that take of authenticity, “This is who we are.” These culture docs are living documents. They’re constantly reiterated. Every culture doc we had at WorkMarket, every time I was with people on a team level, having a team lunch I’d go, “Is there anything anybody wants to call bullshit on? You say this but we don’t do it.” If we don’t do it then either we shouldn’t do it or we should stop saying it. I’m good with either one, quite frankly. As the person running the company, I will make the decision as to which one I think is optimal. If it’s not for you, that’s fine.

You share the culture document when you’re recruiting people. You use the culture document when you’re promoting people and you’re giving them raises. If you’re not doing everything you say then the proverbial brilliant jerk is getting promoted. Everyone’s going to be like, “Collaboration isn’t important. You say it is but clearly, it isn’t.” You have to be authentic.

If you’re doing all those things, which most companies are getting wrong because they’re not codifying the document, it’s not clear to everybody who they are, why they’re here, where they’re going. Even for someone who preaches this, when ADP was buying us, they interviewed all my employees. Not to interview for their jobs, they just wanted to talk to everybody and they did. I was like, “Talk to everyone. Do whatever you want. We’re an open book.” They came back to me and they said, “We asked everybody what is WorkMarket and to describe the company. Here are 72 different answers.” We had about 200 employees at the time.

It was like a kick in the gut. I thought everybody knew the sentence I said but because I said it every now and again, I didn’t have it on a document they looked at every team meeting. Subsequently, every team meeting started out with who we are, why we’re here and where we’re going. I want them to understand who we are, that one sentence. I want them to be able to sing it. I want them to understand why we’re here. Why do you get out of bed every morning and come to this company? I want them to understand where we’re going. I want them to understand what our North Star is because I want them to go and make their own decisions and be doing things. I want to tell them what that has to be done and they can determine the how.

They’re on the front lines. They’re talking to customers. They’re having a billion conversations that I’ll never be privy to. This is something that a lot of companies get wrong, who we are, why we’re here, where we’re going, our values and all the behaviors, policies and procedures that support them. If you’re doing that, you are building the glue between your organization. It doesn’t matter if you got a bunch of gig workers. It doesn’t matter if the teams are remote, it’s hybrid work and you’re not seeing each other all the time. You will be able to maintain that culture and that productivity if you are very clear about what that culture is. That is my answer to your question.

[00:31:20] That’s why we created a podcast, Hosts for Hire. What we do is internal podcasts for large to enterprise-level companies. It’s part of what we do. They’re internal. They’re behind closed doors. They are on secure servers. It enables large organizations to hear from the horse’s mouth what’s going on in different departments, divisions, countries to make sure that purpose and culture issues, new product development and DEI issues are dealt with to be able to have a better understanding of the story so every employee can tell a story. It is so important that employees understand the brand story, where you came from, where you are, where you’re going and why what I do matters. That’s brilliant.

[00:32:11] When I tell people this, I’ll say, “When you think you’ve said it too many times, you’re about halfway there.” I was 100% sure that every single one of WorldMarket’s employees would have said, “WorldMarket Enterprise Software enables companies to organize, manage and pay their freelancers.” Legitimately, nobody did. There are 72 answers but none of which were my sense. I was like, “What did I do here? I wasn’t saying it enough. I was doing it.”

[00:32:44] It doesn’t have to be that exact sentence. It has to be the nuance of that sentence that tells people exactly what you do and how you do it. Everybody’s going to tell that story slightly differently but it’s got to be a great story and that’s the important thing.

[00:32:59] To highlight this because people will go, “What difference does it make?” There were people in my team that was saying, “We’re a marketplace for labor.” Here’s a very important distinction. I appreciate that I called the company WorkMarket and that was mistake number 1 of the 10,000 mistakes I made while building this company, but we’re not a marketplace.

If you are a salesperson and you’re going out there, you’re talking to a customer saying, “We’ve got a marketplace full of people,” they’re going to think that we do and we don’t. It’s a nuance. Are you a marketplace or a platform? No, we’re a platform. That’s why that word was so important in that sentence because I had people out there talking to customers and prospects, saying we were a marketplace. Those people would come on and they would be disappointed.

[00:33:39] Grand confusion.

[00:33:44] To your point, the exact words don’t have to be perfect but it’s the narrative of who we are that is super important. If everybody is not aligned then you don’t have your team rowing in the same direction. You’re not going to get to that North Star.

[00:33:59] How’s the best way for people to get in touch with you? Is it through JeffWald.com?

[00:34:05] I’m super psyched that you went there. It is a new site but yes.

You will be able to maintain that culture and that productivity if you are very clear about what that culture is. Share on X[00:34:09] I love it. It’s clean and beautiful. You did a nice job with it.

[00:34:13] I bought that URL in 1997, maybe 1996. It took a solid twenty-plus years to get content up there, and that is the best place to get in touch.

[00:34:28] One last question, then I’m going to let you out the door. When you leave a meeting, you get in your car and you drive away, what’s the one thing you want people to think about Jeff when you’re not in the room?

[00:34:40] I would want people to leave that meeting thinking we accomplished our goal, that it was an effective use of time sitting with Jeff. That is why I start every meeting by saying, “What is the goal?” If it’s an internal meeting, there has to be a goal and an agenda on the meeting invite. If it’s an external meeting, I will say, “What’s the goal of this conversation? We’ve got 30 minutes together. I want to make sure we hit your goals.” People sometimes are taken aback. They’re like, “We wanted to ask for your advice on this thing.” I’m like, “Let’s do that.” As I get in the car and drive away, I hope people say, “We hit our goal. That was an effective use of time.”

[00:35:28] This has been an enormous efficient use of time. Jeff, thank you for being on the show. Thanks for being such an amazing guest. Thanks to Mark Hershberg for putting us together. He did not disappoint, Mark. I promise you.

[00:35:42] Thank you so much for having me. It was super fun.

Important links:

- Jeff Wald

- The End of Jobs: The Rise of On-Demand Workers and Agile Corporations

- Mark Hershberg

- WorkMarket

- JeffWald.com

- LinkedIn – Jeff Wald

- Twitter – Jeff Wald

- https://www.Amazon.com/End-Jobs-Demand-Workers-Corporations/dp/B08DPYL4KG/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=jeff+wald&qid=1633886139&sr=8-1

About Jeff Wald

Jeff Wald is the Founder of Work Market, an enterprise software platform that enables companies to manage freelancers (acquired by ADP).

Jeff Wald is the Founder of Work Market, an enterprise software platform that enables companies to manage freelancers (acquired by ADP).

Jeff has founded several other technology companies, including Spinback, a social sharing platform (eventually purchased by salesforce.com).

Jeff is an active angel investor and startup advisor, as well as serving on numerous public and private Boards of Directors.

Jeff is the author of the Amazon Best Seller The End of Jobs: The Rise of On-Demand Workers and Agile Corporations.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Community today: